Spotlight 14: Enis Koch

- archigrammelbourne

- May 13, 2025

- 8 min read

Spotlight aims to promote student and graduate work and design. We recently caught up with Enis Koch, a M.Arch student at the Melbourne School of Design, to discuss his thesis project, Sacred Shapes. Enis is highly technical and has a background in Interior Architecture, with a First Class Honours degree from the University of New South Wales, and is currently working at Bates Smart Architects.

-

Christina Garbi (CG): Your path into architecture hasn’t followed the conventional route. Could you tell us how your background in Interior Architecture, alongside your work experience in Cambodia with Habitat for Humanity, may have influenced the way you think about design?

Enis Koch (EK): My journey has definitely taken a unique path throughout the years. My formative years in Interior Architecture had a heavy focus on individuals in space—physically, mentally, and emotionally. Some of our first studios were much more abstract and emotive than traditional architecture studios, and we were encouraged to redefine a lot of preconceived ideas around space, regardless of scale. As my understanding of architecture and design developed, I felt I was always able to maintain this thread of personality through my works. With UNSW being so interdisciplinary, they always fostered that approach. Having visited Cambodia twice, once for a design studio and again as an intern with Habitat for Humanity for a social housing project, occupation and use of buildings became a key interest of mine, and some of the interventions we proposed weren't even architectural; they varied from policy changes to opening up closed buildings for public use to discussions around how we understand heritage its different forms and contexts.

CG: Your thesis “Sacred Shapes” aims to redefine traditional religious architecture within a contemporary context, harmonising rituals of diverse faiths with place. What developed your interest in this idea? Are there any specific design references that influenced you?

EK: The idea for Sacred Shapes was largely influenced by my multicultural background and the diverse religious and cultural architecture to which I was exposed while growing up. My family is rooted in both Turkey and Serbia, which had a profound impact on the architecture I encountered during my upbringing and in my thesis, I drew heavily on these experiences, referencing precedents that weren’t necessarily iconic or widely recognized but held significant power in how they became very ad-hoc spaces for groups to come together. My project focused on redefining traditional religious typologies and making them more integrated into the wider community. This was largely inspired by a competition project I worked on involving a 19th-century church in Melbourne. The aspiration was to transform it into a more public precinct while still maintaining its role as a home for the religion, but through a much more contemporary lens. Our conversations revolved around how this typology had religious precincts which were much more closed off, which highlighted the potential for architects to have a say in how these programs developed.

CG: Your thesis investigates the needs and rituals of various faiths. What are these faiths? How did their needs inform the design and at what moments do they overlap and harmonise?

EK: The project investigates the core values shared by the Abrahamic faiths—Islam, Judaism, and Christianity—drawing heavily on their shared origins in Mesopotamia, the birthplace of these "desert religions." The design references the ancient forms of the desert, such as Ziggurats, as material influences that represent each faith both independently and as part of a cohesive whole. Beyond these physical commonalities, the design delves into the overlapping behaviours and rituals that reflect their shared roots. A significant theme is their relationship with water, whether for physical cleansing or ceremonial purposes. For example, Islam's requirement for ritual cleansing before prayer is accommodated through a dedicated ablution area, thoughtfully designed with privacy screens and pathways that create a serene transition space. Judaism's practice of full-body immersion for spiritual purification inspired the inclusion of a more secluded immersion pool, which utilises natural stone materials to evoke a sense of grounding and tradition. Christianity’s use of water in rituals like baptism is reflected in a flexible water feature that can be adapted for different ceremonies, incorporating movable elements that can be opened or closed as needed. These water elements are strategically placed near each other to allow for shared experiences, while still respecting each faith's unique practices. The overlap is most evident in the central courtyard, where these water features converge, creating a shared sacred space that facilitates both individual rituals and moments of collective harmony. Here, the spatial design encourages interaction, allowing for both contemplation and communal gatherings, thus achieving a balance where diversity and unity coexist.

CG: How did your concepts of contextualising diverse religious rituals manifest spatially on your site? What were the key spatial challenges?

EK: The balance of private and public space was probably the most challenging aspect of the entire project—the desired level of privacy for each space would ultimately be defined by the users and with my proposal allowing this to be in constant flux, it meant that I was always having to reconsider each space from a different angle of potential use. I think the most important aspect was to ensure that every person was afforded the same level of agency in whatever space they were in, and this would ultimately allow their rituals to flow more freely in the spaces. I found that from the precedents I studied, the need for prayer or ceremony always somehow made its way, whether it was a cave or a carpark, a few objects did the job. A great example of this was an installation by Nira Pereg called Abraham Abraham and Sarah Sarah which documented a sacred space in Palestine that holds significant value to both the Islamic and Jewish faiths. It was a cave that alternated between being a mosque and a synagogue throughout the year, and would be interchangeable depending on their own respective calendars and own celebrations. I saw it as an example of how a piece of architecture in a difficult context could be not as prescriptive as they historically have been and be a bit opportunistic.

The overall goal from a planning perspective was to establish a hierarchy of buildings across the site for various activities, including private prayer areas, ablution facilities, and communal gathering spaces. The outcome ensures that each religious practice—whether communal or individual—can be conducted in a space that is almost non-biased to any particular group, but rather equally interchangeable.

CG: Your proposal aims to integrate and harmonise multiple coexisting cultures and faiths. What were the broader community challenges for inclusivity?

EK: While bringing together diverse religious groups presented its own set of contradictions, the more significant challenge lay in fostering a sense of inclusivity and integration with the broader public of Sunshine. The area is undergoing rapid development, with new civic and residential zones continually emerging. Positioned at the heart of this transformation, my site needed to accommodate growth alongside the evolving community. This necessitated designing a flexible space that could adapt to the diverse needs of new residents and act as a catalyst for a new typology. With an influx of people from various backgrounds entering the area, the goal is for them to shape and redefine this space over time, much like they will with the broader suburb, allowing the project to remain relevant and contextually embedded throughout its lifespan.

CG: The design proposal captures a duality between ancient and contemporary architectural forms. How did this influence the form and materiality? Can you give us examples of where you have achieved a harmonious balance between contradicting built forms?

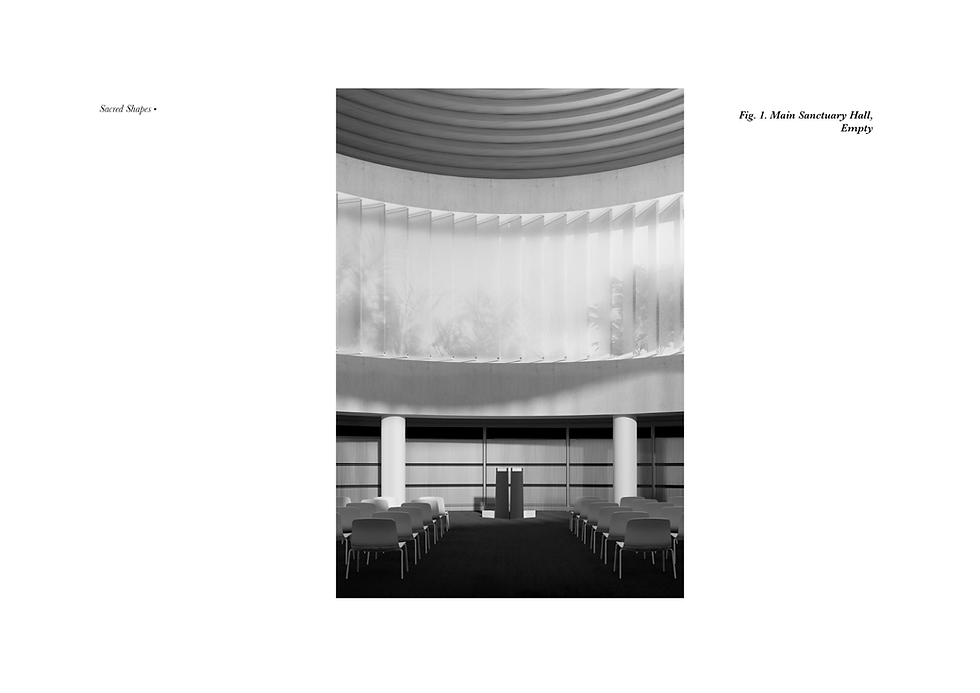

EK: I think the clearest example of the balance between ancient and contemporary architectural forms can be seen in the plan. The main sanctuary, designed as a circle within a square, began to establish a hierarchy within the project. The circle, an ancient symbol of unity, became a recurring motif that harmonised well with the project's intention. This motif was adapted into a contemporary context by being utilised as a tool to manage privacy within the functional spaces. The use of movable doors and walls allowed for varying experiences within the space, creating layers depending on the desired level of privacy. Moving to the section, the interplay between ancient and contemporary is further expressed through circular apertures that introduce soft, diffused light into what is otherwise a monolithic, heavy form. This contrast between the ancient symbolism of the circle and the contemporary monolithic structure creates spaces that transcend specific religious connotations, capturing a universally sacred feeling understood across different faiths. The result is a harmonious blend of the old and the new, where the spatial experience resonates with both ancient and modern architectural languages.

CG: Your project which was exhibited at MSDx demonstrates a thoughtful use of layering and printing of drawings and images using tracing-paper. Could you elaborate on this choice of presentation? How does it aid your concepts?

EK: My decision to use tracing-paper stemmed from a couple of key ideas. I wanted to visually capture the complexity and depth of interfaith interactions within a single architectural space, emphasising that each area was thoughtfully layered with different perspectives. Additionally, I aimed to introduce a bit of ambiguity into the project. I didn’t want to present it as fully complete; instead, I wanted to suggest that it was an ongoing attempt to evolve a typology, making the project more about sparking thoughts and ideas rather than culminating in a definitive built form. The use of tracing-paper to overlap images also demonstrates how multiple religious practices can coexist and interact in the same space without losing their distinct identities, and actually enhancing them. I also kept to quite a restraint palette throughout the project, which meant there was a lot of dark linework, and they become so much more clear when printed on trace.

CG: From developing your thesis, what have you learnt that could be applied to the architecture industry as a whole, on the topic of coexisting inclusivity and representation?

EK: From developing my thesis, along with all my architectural education and professional experiences over the past few years, I’ve come to realise that architecture, while a powerful medium, is not inherently flexible. To truly benefit the industry, we need to develop strategies that allow buildings and spaces to evolve alongside the cultural and societal shifts they house, and understand that each project plays a larger role in the architectural and social contexts that they’re in, meaning it may take a few projects to get a message across or have any noticeable impact. It also means engaging more deeply with communities during the design process to ensure their voices and needs are not just met, but actively integrated into designs for years to come. By embracing this, architects can actually allow new communities to arise. I think we are so quick to propose co-living or co-working situations, but that doesn't seem to extend to other architectural typologies, and my project seeks to ask why.

CG: What else is next for you?

EK: This last semester I am writing my manifesto on a similar topic, so it has been good to delve into the theoretical side of the project a bit more. After that's done in November, my goal now is to continue working at Bates Smart towards registration and to start seeing what opportunities come along the way! I feel that every day I am seeing new paths or roles pop up in architecture, so I am keen to see where it could take me.

-

Interview Credits:

Interviewed by Christina Garbi

-

Project credits:

University: University of Melbourne

Year: 2024

Project images provided by Enis Koch

Comments