Spotlight 06: Riley Sherman

- Isabella Paola-Rose Etna

- Feb 5, 2021

- 10 min read

Updated: May 5, 2022

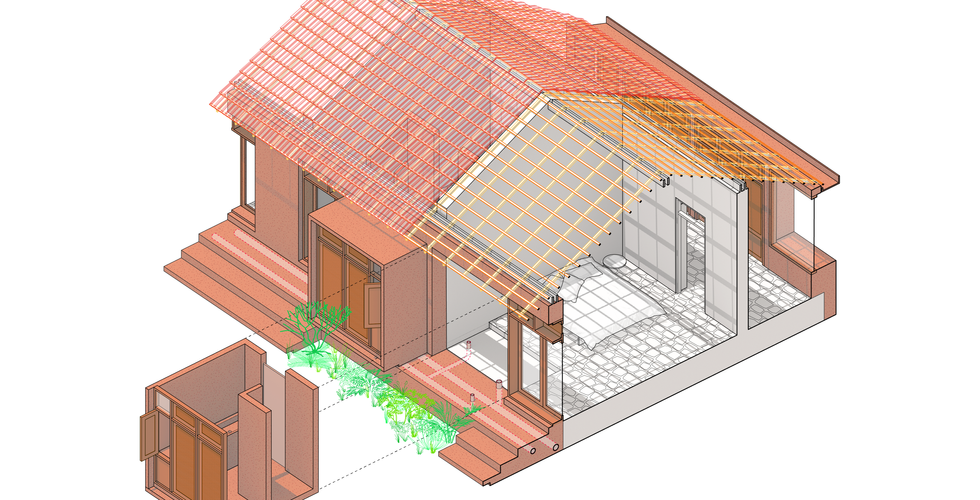

Spotlight aims to promote recent student and graduate work in Design. We recently caught up with Riley Sherman to chat about the design and commencing restoration of ‘Casa Eva’. Located on a teak plantation in Goa, India, the project so far has involved restoring the three-hundred-year-old Goan/ Portuguese house on site and designing an extension that is better fit for 21st century living. This project is an ongoing collaboration that Riley has undertaken with Juliana Vaz.

Riley started his architectural studies at the University of Melbourne in 2015. After completing a year long exchange program in the US at the University of Virginia and his undergraduate studies, he joined John Wardle Architects in 2018 before moving interstate to help the practice establish their Sydney studio.

Isabella Etna (IE): You’re originally from Geelong, Victoria, on the Bellarine Peninsula. Could you tell us about where your passion to study architecture came from, and in what ways you feel that your roots on the Bellarine Peninsula has shaped your design approach?

RIley Sherman (RS): It probably goes back to my great grandfather, he was a builder and project manager working on large-scale projects across Queensland, Melbourne and Geelong. He worked on projects such as Melbourne Central and the Geelong Cement Works, which had been one of the most prominent features in Geelong, a statue to industrial progress on the top of Fyansford hill. Unfortunately they’ve recently finished demolishing it to build a new housing estate in its place. There are no architects or designers in my family so my parents have always wondered where my passions came from, but I’ve always traced it back to my great grandfather. However, the opportunity to study studio arts and visual communications throughout high school is where my passions became tangible. In those classes I discovered my strength for visual communication, and for someone who isn’t as strong with words, it was the place that I found my voice, and for me it was just a natural progression into architecture.

IE: We understand that during your undergraduate degree at the UoM you participated in an exchange to University of Virginia (UVA) in Charlottesville. What impact did studying at UVA and travelling in the US have on your approach to design?

RS: Coming from the Bachelor of Environments at UoM, I had a pretty broad perspective of the natural, built and cultural environments in both the local and global context. This led me to want to broaden my horizons and step out of Australia. I initially chose to study in the US because their programs are renowned for their strong studio focus and academic rigour. At UVA, all students are placed in studio groups and are given a large workstation for the year which creates a studio environment that is lively and provides the opportunity to interact and problem solve directly with your peers around you. It’s very similar to how architectural practices operate and I found it really engaged my passion for architecture, which I wasn’t initially finding with the program back in Melbourne. Both pedagogical approaches have positives and negatives, but I found having the opportunity to engage with a smaller group of peers on a regular basis who are all interested in different aspects of architecture, in one creative space just felt like a more natural way to learn about architecture. This studio environment also enabled me to work much more closely with professors and people with extensive practices in architecture. The coordinator for my second-year foundation studio was Alex Wall, who worked for OMA in the 80s and 90s produced the iconic “Pleasure of Architecture” drawings. Coming from an urban planning background, Alex gave a much broader focus to our projects and was great to learn from. One of the most formative professors I studied under was Charlie Menefee who would walk around the studio with his clipboard and as you were talking he would draw something as a way of providing feedback, instead of telling you what to do or what not to do, instead of words, you got a sketch. His emphasis on drawing really developed my own process as I saw the power of sketching and learning the process of drawing and modelling.

I really benefited from being exposed to both styles of learning; the broad based academic approach from UoM, and the year at UVa where it was hands on studio based learning. However at UoM I found myself relying on YouTube to find out how to use certain programs or drawing techniques, or messaging my friends because they weren’t studying on campus. It was a very artificial way of learning and a large barrier to a productive studio culture. You really need a space where people can interact, meet and learn from each other to create ‘studio’ culture. It can be difficult to motivate yourself, but when you’re in a shared and creative space, that type of environment can be just as valuable as what you’re learning. I think if Australian institutions want to actually help and support architecture students, they should start by reestablishing the studio and reintroducing an environment that encourages connection, teamwork and learning from one another. It’s the same thing I have learnt while working in practice, you learn the most from the people around you. Having others who are passionate about design around you, and who push you outside of your boundaries is the most important thing, not just as a student but in life. It’s so important in this field to diversify your perspective, you need a myriad of ideas, perspectives and people around you to do so.

IE: In 2019, you had the opportunity to collaborate on a project in Goa, India with friends. This is such an amazing opportunity for a young designer, and something that most would probably dream about. Could you tell us about how this happened?

RS: My friends, Juliana Vaz, Sherina Jhunjhnuwala and I had been talking about collaborating on this project since the start of 2019, when we went back to Virginia to celebrate our friends’ graduations. Juliana had been thinking about the project for many years, so for me, while it was a risk, I saw it as an exciting opportunity to help make Juliana’s dream a reality. Juliana’s family who are originally from Goa, and are now mostly located in Mozambique, have a historic Goan/ Portugese villa in Goa that has been passed down for generations since 1741. It’s located in the South of Goa, on the western coast. It’s a ten minute walk from the beach in Colva’s 1st Ward. The house is unbelievably beautiful, located on an overgrown teak plantation and surrounded by giant trees. Casa Eva has been sitting empty for almost ten years and it’s always been her dream to restore and reimagine their family home into something that is productive again. Part of the brief was to create five main bedrooms with ensuites to accommodate the extended family, and while we were discussing the logistics of the home, we were also imagining new ways for it to adapt and function in the future, which was the most exciting part.

Image: Goa, 2019, provided by RIley Sherman while on site in Goa, India.

IE: Could you elaborate on the brief and site including the restoration, adaptive reuse and extension of an historic Portuguese Goan House?

RS: We had really large aspirations at the beginning, whether there was an opportunity for it to be a community art space, or an artists residency and hotel. However, the way we have designed it was for it to be flexible, so we don’t have to work on the broader scale at this stage, and instead focused on saving and restoring the main house. We started the design process before I moved over to Goa, but I found it so difficult because I didn't have much understanding of context, its history or the proportions of the space. Context is so important, especially when you’re working with historic fabric. Another friend is working at an engineering firm in New York and they have an office in Mumbai, so they came down and did a 3D scan of the house, so we had a cloud point model to work with, capturing it in its existing state. Although we had that in December of 2019, I still found that quite difficult to design anything because I didn't understand anything about the climate, or context. We decided that the correct way to stage the project would be to focus on the critical restoration works first (Stage 1). This included reconstructing the entire roof, new plumbing and electrics, which sounds simple but is quite complicated in a house with solid laterite and mudbrick walls that were built in 1741. They also have a severe monsoon season which put major time constraints on the project. Unfortunately, it’s not like Australia where you can be on site throughout the entire year. We managed to complete a majority of the restoration work on the roof which involved the contractors disassembling the roof, replacing timber that has been damaged by the weather and finally putting it all back up. This was also completed in the middle of the pandemic which really slowed progress down and has delayed the next stage of the project which will include the main extension of the living quarters, where a majority of the architectural interventions will occur.

IE: How would you summarise the kind of design approach you’ve taken on the Goa project?

RS: Part of the reason I wanted to move to India for this project was because I’ve come to realise that contemporary approaches to architecture aren’t the best benchmark. We should be looking at ways of designing that are socially, economically and environmentally sustainable, and there are so many solutions that already exist. For example, we learnt from a local builder that if we coat our timber in cashew oil it deters termites, which are a serious problem in Goa. Further, we discovered that the house was originally lined with lime plaster and that it deters ants. It doesn’t seem like much of an issue in an Australian context where ants are a pest in our pantries, but in Goa ants are quite large and can burrow into tiles and cause quite a lot of damage. All of these little things that we learnt show us that a lot of our problems can have low-tech solutions, if you know where to look for them. The house itself is quite interesting, and has been a great case study to learn from. Our design, the extension to the house, adopts a more local language from the Goan the courtyard house. The project is interesting because it raises the question, at what point is the architecture local or at what point is it imported? You can reduce the value of the original house by calling it “Portuguese,” but it is unique in the sense that it exists in Goa, and now we, an Australian and a Mozambican are designing a new courtyard extension to the original house. That has always been an interesting aspect of architecture. We always think that once we put the pens down that something is finished, but architecture will always have a much longer life cycle than we do (hopefully). So it’s always open to interpretation and different inputs.

IE: As a young designer and only a few years out of your bachelor degree, what do you feel you’ve learnt from this experience?

RS: Definitely that resilience is an important part of architecture. Being able to adapt to changes is something that I learnt while working at JWA (John Wardle Architects). Whether it was the client changing their mind, a site challenge, or a pandemic, you have to be able to pivot and adopt your creative process. In University, as students you only ever experience a 3 month studio project, but in practice, projects can take up to three-five years or even longer. Being able to persevere is so important because architecture always has its challenges and we need to be able to respond and adapt to them. One of the issues in Goa is that there is no waste system, which made us really consider the way we approached the restoration and design of the house, so it became about retaining as much as we could of the existing extension (built in the 70s or 80s). We realised when we were on site, and seeing the situation in Goa, it completely changed our design approach. It’s given me perspective on how we should use materials, and how it's our generation's responsibility to work with materials in a more sustainable way; minimum intervention for maximum output. It’s not just thinking about the finished project, but the impact of the project as a whole from a life cycle perspective, and asking ourselves what materials are we putting in or what are we wasting. We need to approach architecture in a different way because we don't have the luxuries of past generations.

IE: Coming back to your studies in architecture, after graduating from The UoM in 2017 you have been working at John Wardle Architects since. Could you tell us about why you decided to take a break between further studies in architecture?

RS: I never intended to take three years off between my undergraduate degree and master's degree. Honestly I was just following where the opportunities took me. I always knew I wanted to take at least a year out, because I had no experience working in practice throughout my undergraduate degree and always felt nervous about it. I knew it was important to get some practical experience because I knew that ‘architecture’ was totally different to what we learn at university. Since then I had the opportunity to move to Sydney with the firm, and start up another studio up there. Again, it seemed like another good opportunity to get a new perspective. JWA is quite a big firm and people talk about the difference between working in a small practice and large practice, so in a way I was able to stay within a bigger practice but get that smaller practice experience at the same time.

IE: You also relocated to Sydney with JWA, could you tell us about this experience and how it prepared you to take up the project in Goa?

RS: Moving to Sydney was definitely a challenge because the Melbourne Studio was working like a pretty well oiled machine, as expected from a well established practice that has developed its design process over the past thirty years. When I moved to Sydney there were strands of similarities in the way of working, but things changed quite drastically because we were working in a new city, and under new conditions. It's important while working in architecture to be adaptable and I’ve always been someone who likes to step outside of their comfort zone. Moving to the US was the first time I’d ever left Australia, and after my first year at JWA, taking the opportunity to move to Sydney allowed me to see a different side of practice altogether. So much more happens in the practice of architecture than just making buildings. John (Wardle) always emphasised this idea of stepping outside the boundary and beyond the building to see how architecture can do more for a city or the community.

There was definitely a progression from working in a large studio, then going to a much smaller team in Sydney which I really enjoyed. I had great mentors and was able to learn a lot from them. I did take on more responsibility which was an experience that prepared me well for India, however I was a little terrified to move over to Goa because it’s a new country, I didn't speak the language, and it was going to be the first independent project I would be designing. However, I took the risk, I loved it, and I can’t wait to get back there one day soon.

-

Project credits:

Casa Eva is an independent project undertaken by Riley Sherman and Juliana Vaz

Schools (previous/exchange/current): Faculty of ABP, University of Melbourne / University of Virginia School of Architecture

Project images provided by Riley Sherman and Juliana Vaz

Follow Riley’s Instagram @rileysherm for more updates

Comments