Spotlight 04: Panphila Pau

- Isabella Paola-Rose Etna

- Oct 7, 2020

- 7 min read

Spotlight aims to promote recent student and graduate work in Design. We recently caught up with current MSD M.Arch student Panphlia Pau to chat about her exchange to the University of Sheffield, how her Hong Kong heritage has shaped her design approach, her love for watercolour and her studio project for the Master of Architecture at The Melbourne School of Design.

Panphila grew up in metropolitan Hong Kong, where she says that the city is abundant with grass you can’t actually walk on. Since moving to Australia, she’s now capable of walking barefoot outside and squashing bugs with her hand.

Isabella Etna (IE): In 2018 you went on exchange to The University of Sheffield in the UK. Did this experience studying abroad influence your design approach?

Panphila Pau (PP): Yes, in particular there was one special place that completely changed the way I think about architecture. It was the Sheffield Institute of Arts. I’d say it was the most influential place that I visited during my time abroad. It’s situated adjacent to a public square with one or two statues there. It seems to have had many lives over it’s 170 year life span, it even was a post office for 90 years until 1999, but had since been revitalised in 2016 and given new life as an institutional building, with silversmiths and metal workers. It’s a place that fosters a sense of community and place for artists and makers, but also for learning and industry contribution. Beyond this, one of the biggest takeaways for me was that heritage and heritage conservation is so important in the UK, and is unlike what I’ve grown up around in Hong Kong.

Image: Sheffield Institue of Art Building, 2018, captured by Panphila Pau

IE: You’re originally from Hong Kong, a city with an influence from the East and the West, and an eclectic fusion of architectural styles. Could you also tell us about how your home city shaped your approach to design?

PP: Hong Kong is a rapidly developing place, although it was previously a British colony, but the way the city has developed over time can now be described as homogenous, you wouldn’t believe how many curtain wall high rises are in the city. What I learnt not only from my studies at Sheffield, but also by experiencing English cities and their architectures was that there in contemporary design education over there that there is a huge focus to take into account the pre-existing context and life of the city; the people who inhabit it, site characteristics and they revere context. I found this really difficult to grapple with because it was so different to what I had learnt “what architecture is” back when I did my bachelor’s at City University of Hong Kong. What I mean by this is that we had history classes during my bachelor’s, but there was barely any focus on heritage conservation and factors like prior building use over time. We had so much design freedom in my bachelor’s degree so it was quite difficult for me to adapt to this new, and completely eye-opening mindset on heritage. Having this in my mind going back to Hong Kong after the exchange, made me wonder why there is an obsession with the “new” and why it’s often equated to “progress.” Why can’t we appreciate and celebrate the existing city fabric? There is one particularly good example of this in Hong Kong. It’s called Tai Kwun, where a police station was reimagined as an arts and cultural centre by Herzog De Meuron. In the early 90’s when Hong Kong was still a colony, Tai Kwun was a prison. It was converted into a police station, and now it’s recently been transformed into an arts and cultural centre, with civic and hospitality offerings. The amazing thing is that the original prison layout has been preserved, but a new program has been inserted, so all of the cells and bridges/footpaths as it once was when used as a prison. There is almost a new life that’s been ejected into the complex, while also providing a mix of functions that gives back to the city. The new square has been successful to encourage civic activity and public gatherings. The Herzog De Meuron facade is also quite successful in the sense that it blends in well with the surrounding context, it’s not an awful eyesore. By contrast the development at Lee Tung Street is an example of how a wonderful naturally developed local vernacular architecture was not celebrated. It’s demolition was a missed opportunity. In Hong Kong it’s common for shops to have precarious and questionable looking sign structures, usually signs are made using a thin steel rod with two strings and finally the sign, which usually lights up at night. Lee Tung Street was previously the site of a dilapidated marketplace that was completely ad hoc in composition. It was almost grass roots in the sense that neon signs were overhanging one and other as different small retailers competed for space. It’s now demolished, and has been replaced with an avenue flanked by Parisian looking buildings with small retailers that try so hard to emulate a European or colonial atmosphere. This is the sad approach of many developments in Hong Kong that neglect the local vernacular, and exclude the beauty of local “messiness.”

Coming back to the Sheffield Institute of Arts, it was influential on the studio project I undertook while on Exchange, and I still carry these values with me into my current projects. Not only did I find the heritage conservation aspect of the building fascinating, but I also found the program fascinating, especially the way that craftspeople and learning comes together, and I wanted to emulate these things in the project I undertook while studying abroad at UoS. I found it fascinating how the program attracts public attention to know more about arts culture.

IE: Your recent studio project Hippy Hoppy Home for Studio 16 by Joel Benichou explores “insidesness and outsiderness in thinking of being and non-being”. Could you elaborate on this?

PP: Each student was asked to design our own client brief for a residential complex in Kew on the Studley Park Vineyard. I was interested in the idea of how historically in the 1970’s in Hong Kong running a family business was a very common thing, it was a socio-economic pattern during that period, and the typology associated with it is called Tong Lau, but also referred to as tenement houses by the British colonials. It’s a four to five storey high building where the upper floors are for dwelling purposes. The ground floor is where the family business is located. Whether it be a home style restaurant where they could be selling cart noodles or other local cuisines, or a shop that sells goods, it’s basically a place for locals by locals. Nowadays in Hong Kong family businesses are dwindling away because most of the younger generations just are not interested in running them, while the socio-economic landscape has completely changed. I wanted to explore this sense of nostalgia through my project, because there really is a sense of beauty and local memory embedded in this typology that I just couldn’t get away from.

Coming back to the site which was located on the edge of Kew and Collingwood, in the Eastern suburbs of Melbourne just across from the Yarra River. I looked at the local features of Collingwood. Historically Collingwood was a working class suburb. The historical industry there was the manufacturing of goods including perishable goods, and the two historic breweries including The Yorkshire Brewery (1861) Fosters Brewery (1888). They represent the conception of the brewery culture of Collingwood, that despite not remaining intact, are evident today in the abundance of micro breweries that exist in the area today. Kew on the other hand, is a more family oriented suburb.

I wanted to combine these three characteristics on my site, where my nostalgic interest in the Tong Lau typology meets the Brewery culture of Collingwood, but also the family oriented nature of Kew. So naturally my focus for this studio was on a multi-generational home and family business, which I designed for a family of six. The Studley Park Vineyard, is where Hops Bines grow, which is the essence of the family business. The complex also offers a tea drinking house that specialises in site harvested Hop Tea. Hop Tea is basically a non-alcoholic beer. I wanted to create a much more family oriented destination and introduce a new drinking culture to the community.

Image: Hippy Hoppy Home, Semester 1, 2020, provided by Panphila Pau while participating in Studio 16, Melbourne School of Design.

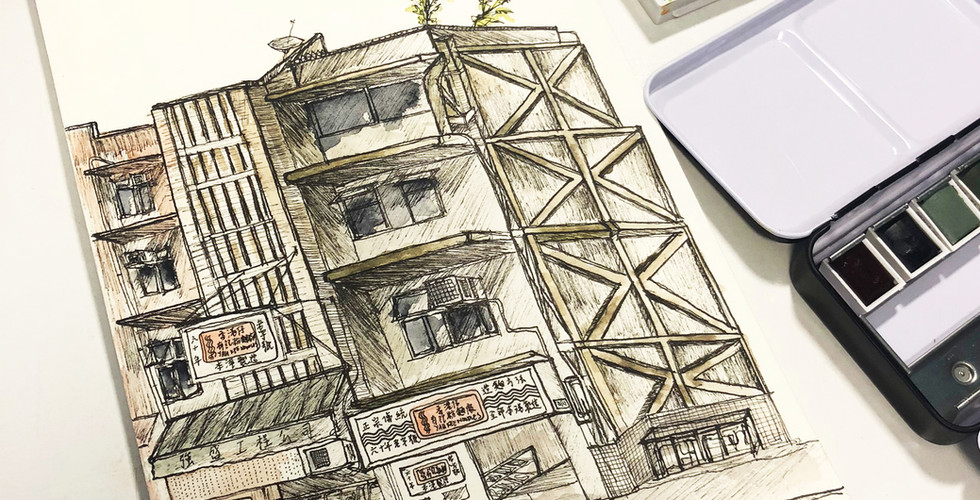

IE: Aside from your studies in architecture it is clear from your personal Instagram account @yppan.pp where you have posted your watercolour paintings from your travels, that you have an interest in observing and representing the world around you. What role does this play in your design process and approach?

PP: In this day and age with our smartphones it’s so easy to take a million photos, and to never look back or to stop to reflect on those moments, to embrace the detail of moments. I usually buy postcards from the different cities I travel to. I use them to draw things on the blank side, and I collect them. I also do simple sketches in a sketchbook. Everytime I look at my sketchbook or the postcards and hold them in my hand the memories of being in those foreign places, in the hot sweaty climates, and holding the same sketchbook in my hand, vividly flood back to my mind. I love doing it because it let’s me transport back to those moments. I remember I wanted to capture the Santorini sun setting in a series of quick watercolours in my sketchbook. I had to do it quickly because the sun was setting quickly. I remember that memory, the place I was and even the temperature when I hold my sketchbook today. I use this technique to record the impressions that moments in foreign places have on me, so that I can easily recall those moments and the emotions I felt during those times from the quick flick of my sketchbooks.

IE: On the topic of representation, would you say that watercolour techniques have influenced your style of representation in your Studio Projects?

PP: When you do a watercolour painting you have to be so aware of how much water you are putting on your brush, the techniques of layering and the order you apply colours from foreground to background (or vice versa). I’ve carried my awareness of these techniques into my studio projects. In my Hippy Hoppy Home Project I focussed on using yellow and green as the dominant colours on my panels. I tried to relate it back to what I had learnt about colour theory while producing watercolor impressions. Where yellow represents my nostalgia for the Tong Lau, a cosy warm comforting feeling, and where green represents the leaves of the hop tea. Although it was a natural choice for me, when I think about it I can see myself constantly bringing in my knowledge of watercolour and art techniques into my project representation.

-

Project credits

Hippy Hoppy Home by Panphila Pau

School: Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne

Studio Leader: Joel Benichou

Year: Semester 1, 2020

Level: Studio E

Project images provided by Panphila Pau

Comments