Opinion 12: AI Architecture

- archigrammelbourne

- Jul 9, 2024

- 11 min read

By Tom Davies

One step back, two steps forward.

“AI is a powerful tool that can assist architects in various aspects of the design process, but it is not necessarily better than humans at architecture... it cannot replace the skills and expertise of human architects. The most effective approach is to combine the strengths of both AI and human architects to create innovative, sustainable, and socially responsible designs.”

-Artificial Intelligence.

How modest.

Over the last year, artificial intelligence has been wreaking havoc in online, professional, and educational communities. In the world of Architectural design, this explosion has been navigated at a more personal level as designers began to contrast the capabilities of the various AI’s against their specialisations. In the wake of the chaos, the age-old question reverberates once again,

Can a machine do what we can?

I would like to begin by defining what AI means in the scope of this piece. I will be referring to AI as word-based and pixel-based subset statistical models referencing large data sets known as ‘Big Data’ (Mashey, 1990) that use pattern recognition and machine learning (ML) to produce results based on the said data sets. This is known as deep learning and, generally speaking, relies upon the algorithm making connections between inputs and outputs. This differentiates itself from mainstream symbolic and rule-based AI such as ‘GOFAI’ (Haugeland, 1985), meaning “Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence”, which requires human intervention to establish rules of correlation.

In his piece, ‘The Advent of Architectural AI’ (2019), Stanislas Chaillou presents the emergence of AI as a “Four-Period Sequence” under the umbrella of what is referred to as “systematic architectural design” (Chaillou, 2019). Beginning with Modularity, an idea theorised by the Bauhaus’ Walter Gropius, this refers to the use of grid planning that affords simplistic design and assembly yet leaves room for rigour at the human scale. This catalysed the second stage, Computational Design, which saw the development of CAD. The third stage was the emergence of parametric architecture in 1988 which responded to exponentially increasing regulation and urban density. Where it fell short was its lack of theoretical understanding as it could not consider data-driven processes like social, cultural and conceptual factors and thus we saw the emergence of the fourth stage, AI.

Therefore, it can be argued that AI applications in architectural design have arisen in attempts to look beyond responding to a predetermined series of parameters to instead utilise a “learning phase” that uses the brain “as a model for machine logic” (McCarthy, 1956) to generate design outcomes based on a complex statistical distribution; a key downfall of parametricism. But how has it begun to manifest in today’s industry, an architectural zeitgeist riddled with issues of scale, density, and societal expectations far exceeding any epoch to date?

So we know now that the potential power of AI in architecture surrounds the statistical distribution of big data and layers of subsets within that as well as how machine learning can recognize patterns and emulate human-related intelligence autonomously to pass the Turing Test: A test that deduces whether or not a computer is capable of thinking like a human.

To expand my understanding of AI beyond how it’s painted in the media, I caught up with Loren Adams, a Computational Dominatrix and Robot Overlord, at the University of Melbourne.

Having experienced frustration with both Melbourne and Los Angeles’ poor low-cost housing models, caused by “enshrined apartment guidelines that are so detailed that it leaves no room for nuance or intervention”, Adams sought to explore a poetic AI-driven reinterpretation of building regulations in her ongoing RMIT studio ‘Regulatory Nonsense’. The framework for this exploration was compiling a big database of poems and exploring the open-ended “glitches”, in this case, reimagined regulatory building frameworks, that the AI would produce through a poetic lens. We engaged in a discussion surrounding the purview of AI in the architectural sphere. She highlighted the dangers of AI as being an unpredictable and non “generalisable” tool that has been overshadowed by a rapid influx of “AI hype”. This expectation that AI can simply produce results autonomously is an unrealistic assumption that has led the term to be grossly redefined in popular vocabulary leaving us “on the back foot” as the hype has “created so much delusion that we have to spend time reigning in these delusions”.

A key point of discussion was Bates Smart’s ‘Digital Muse’ (2023) exhibition within Melbourne’s Design Week program. Their synopsis:

“Experience a showcase of innovative Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems exploring their imaginings of our built environment. Discover novel versions of familiar Australian places that highlight new applications of AI technology, offering a glimpse into potential alternate histories and futures.” - Bates Smart

The exhibition used pixel-based data sets from Midjourney to reimagine iconic Australian landmarks in a futuristic lens with new facades. Whilst impressive at first glance, the truthful nature of these text-to-image open AI’s is that they draw upon influence from works that have been curated with copious labour. Architect works, photographers’ images, and various other digital media that result in an output that pays no homage or reference to the original curators and is no more significant than a “nostalgic repackaging of something that exists” (Adams, 2023).

Similar to Mark Fisher’s explorations of the “end of history” (Fisher, 2012) in ‘What is Hauntology’ (2012), this exhibition presents a key example of anachronism as it is a failed attempt at meaningfully perceiving new architecture. The works are generated from existing buildings, derived from existing works, and are thus no “glimpse” (BatesSmart, 2023) at a new architecture or a valuable application of AI in architectural design. That is not to say these explorations are not insightful in an epoch riddled with demand for innovative thinking to break free from “cookie cutter” (Adams, 2023) design regulation that affords little originality on scales such as co-housing and apartments. However, we ought to be examining how AI can be integrated as a powerful tool of symbiosis that works in synthesis with emerging design processes and not as a separate entity that envisions a new architecture. In the same way CAD, 3D modelling, and parametricism sought to aid the design process, AI must not replace the creative process but instead work in unison.

Another point of oversight from the design community was largely concealed amidst the delusional AI hype and media clickbait. ChatGPT and Amazon both take the spotlight here. Time’s magazine writer and journalist Billy Perrigo wrote an expose in January 2023, titled ‘OpenAI Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make ChatGPT Less Toxic’. As implied by the title, this piece presented readers with the dark methods of filtering that resided in the development of mainstream open AI. Not only were they paying workers a mere “$1.32 and $2 an hour” (Perrigo, 2023), but they also exposed them to highly graphic material for hours on end, scarring them in the process. Amazon was no different with their crowd-sourcing service ‘Mechanical Turk’, a term derived from a fraudulent robot that played chess in the 1770s but was controlled by a human. They set no minimum wage and took a 10% commission and masked them as a digital service. Yet the creative industry has been so hypnotised by the rampant emergence of AI software that we have been oblivious to the detriments of these advancements. Whilst it seems we have moved forward a step, we have taken two back. Despite the overarching storm clouds that currently surround AI, there have been meaningful applications of AI that have emerged. To frame my research I wanted to reference part I of Kyle Steinfeld’s ‘The Routledge Companion to Artificial Intelligence in Architecture’ (2021), he highlights three emerging categorical trends of machine learning:

1. ML as an actor

2. ML as a material

3. ML as a provocateur

Here, ‘actor’ refers to AI as a design “participant” (Steinfeld, 2021) alongside humans, ‘material’ infers the AI’s ability to process big data and abstract relationships within that data, and ‘provocateur’ refers to an AI’s ability to generate design stimulus in the schematic design phase. It is important to note here that at no point is AI presented as a substitute for human processes. An interesting example of AI as an actor is explored in ‘Imaginary Plans’ (2018), whereby Michigan researchers explored the ability to imitate creative neural networks in an AI that led it to produce “dream-like” “hallucinations’’ (Matias del Campo, 2018) of stimulus floor plans that were radically different from the processes typically applied by humans giving it a “post-human” nature. This demonstrated that neurochemical processes in the brain could be emulated in an AI allowing it to produce original plans and design language.

In my opinion however, the most applicable process is using AI as a provocateur. Steinfeld’s Architectural subset code called ‘Sketch2Pix’ is an extension of an existing software called ‘Pix2Pix’ and is a strong example of AI as a provocateur. It uses machine learning processes to create “brushes” that turn sketched ideas into realistic portrayals of the subject matter associated with the brush.

This process, called “Suggestive Drawing” (Steinfeld, 2020) allows for entire sketches to quickly become realistic images through the use of multiple brushes that complement rough ideas, a program useful for propelling a larger design process that compliments traditional architectural mediums such as linework and sketches.

Another major application responds to architectural visualisation. With the infatuation and awes of pixel-based AI sweeping the design community off their feet, numerous AI’s were created in response to match mainstream hype. One particular example is Photoshop’s ‘Generative AI’ update which allows users to enlarge their image crops whilst maintaining the same PPI ratio. If combined with a software such as Sketch2Pix, a designer could sketch an idea, have it be generated into a realistic form using a pool of selected image prompts, as seen in ‘Perceptual Engines’ (2017), then use generative fill to create enlarged context.

Given precedents are a major factor in any architectural design process, there is justification to incorporating Midjourney as a tool in our design processes and has led me to speculate there will most likely be specialist AI roles emerging within the industry over the next decade. This is because, whether it be at the beginning, middle, end, or even throughout the design process, AI will always exist as a tool but we ultimately have to call the final shots and implement a human touch. In order to understand these systems myself - and for demonstration - I made use of the previously mentioned text-to-image generator called Midjourney. Founded in July of 2022 by David Holz, Midjourney is a self-learning AI software that allows people to type “/imagine” followed by an endless choice of sentences or prompts which produce a 2x2 grid of unique images. To start, I created a rudimentary set of parameters to start my explorations:

1. A Style/Origin

2. Subject matter

3. A Material

4. A Random factor

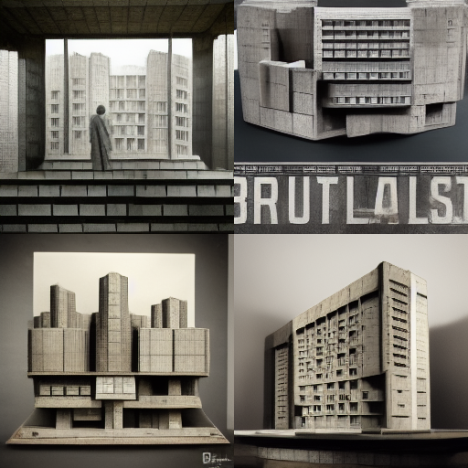

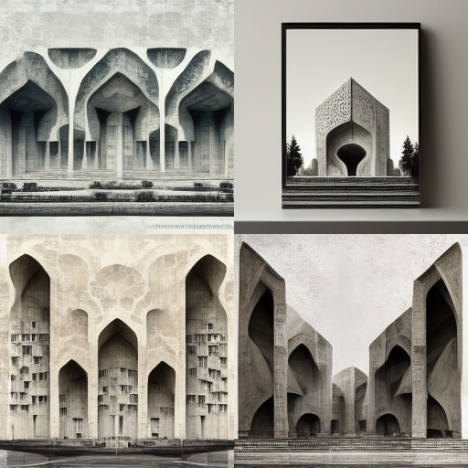

Series A: Collage B: Brutalist building - Scale model - Hyperrealistic - Cinematic Series A: Collage A: Persian - Architecture - Concrete - Inverted

Now that I had explored a vague input I decided to navigate more specific prompts in regards to an envisioned outcome. I decided on two visions; the first was to produce a realistic scale model of a Japanese style building. The second was to test an arbitrary built form which my intrusive thoughts decided would be a brutalist spaghetti and meatball house.

Series B: Collage A: Japanese architectural model - Timber construction - Megastructure Series B: Collage B: ‘A brutalist home made from spaghetti with a meatball chimney’ architecture - Hyper realistic - Realistic - Ultra realistic - Photorealistic - Cinematic lighting

This process brought to light iterative possibilities for schematic design yet I am sceptical whether there is any concrete use beyond testing ideas or generating arbitrary design outcomes. Most image-based AI can now receive visual prompts in combination with verbal inputs. So in order to substantiate this claim further, I experimented with an image prompt I created in Twinmotion which is an empty blank room and asked Midjourney to “furnish this image”.

Whilst it retained the character of the input image, the forms and additions reached beyond the purview of the input. Perhaps with iterative refinement this could become more delicate toward preserving the original image but I declared that the process wouldn’t be much faster than using assets in a rendering software. What the outcome did demonstrate though is the testing of forms. As designers we could quickly generate spaces and use midjourney to investigate potential uses of these spaces.

In an interview mid-way through 2022, Archigram Melbourne Co-founder, Bella, and Editor, Mia, interviewed the founders, Zoe Spooner and Sophie Beckerleg, of RMIT publication, Pisstake Press. “We make zines by stealing thoughts and images from machines through text-text and text-image ai programs, and whipping them into something silly to print.” - Pisstake Press. Their application of both text and image based AI was purely experimental and they didn’t seek to pass off any of the work as original or as their own unlike the firm that has been “designing historic landmarks and contemporary buildings” for “170 years” and have a “team of 300 professionals” that “understand the social, cultural, sustainability, and economic forces” (BatesSmart, 2023). Not sure if irony is a strong enough word here.

In the interview Pisstake Press highlighted their opinion on the use of these softwares, “The point of it is to be like fun and creative and generate ideas and inspiration...It’s not gonna have an impact on design, like finished design, really you can’t really use it for anything concrete.” (Pisstake Press, 2023) It would appear that despite their differing applications of AI, the results aligned with mine.

AI has presented opportunities to speed up schematic design processes and tackle repetitive tasks that AI can learn through big data sets and pattern recognition. Therefore, it can be assumed that AI could be beneficial for smaller firms as it could tackle documentation processes and other back-of-house tasks leaving more flexibility in time allocation to creative processes. Additionally, more time and resources can be allocated to creative processes such as schematic design and devising more innovative solutions to strict planning regulations. This could potentially make larger firms more redundant as smaller firms could compete with the workloads of larger projects.

This would also counter the growing trends associated with documentation outsourcing which has grown in popularity with larger firms as they look to overseas firms to produce drawings for a much cheaper rate. This presents an interesting juxtaposition against other major technological advancement periods the industrial revolution which affected blue-collar workers, but in this instance, AI would challenge the jobs of white-collar workers but simultaneously present new job opportunities associated with the use of AI.

It is clear AI has many limbs, applications, and nuances. Whilst it is still very much on the horizon, a common thread appears to run throughout my explorations. That is that artificial intelligence is a tool that must exist in symbiosis with the architectural profession and unlocks complex data analyses of big data sets unfathomable by the human mind. Additionally, it excels in visual exploration and stimulus, essentially functioning as a provocateur. Above all, we must be cautious not to expect it to create immediate solutions for ongoing architectural quests in a contemporary environment or to replace entire design processes. But instead, we should use it as a compass to navigate and propel our design thinking.

-

Citation:

BatesSmart. (2023, May 20). Ai architecture – Digital Muse. Melbourne Design Week. https://designweek.melbourne/events/ai-architecture-digital-muse/

Chaillou, S. (2021, June 10). A tour of AI in Architecture. Medium. https://towardsdata

Del Campo, M. (2018). Imaginary Plans. Acadia. 412-418. https://papers.cumincad.org/data/works/att/acadia19_412.pdf

Fisher, M. (2012). What Is Hauntology? Film Quarterly, 66(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16

Harris, M. (2014, December 3). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk Workers protest: “I am a human being, not an algorithm.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/dec/03/amazon-mechanical-turk-workers-protest-jeff-bezos

Perrigo, B. (2023a, January 18). OpenAI used Kenyan workers on less than $2 per hour: Exclusive. Time. https://time.com/6247678/openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers/

Reuben Das, M. (2023, January 26). Neocolonial slavery: CHATGPT built by using Kenyan workers as AI guinea pigs, Elon Musk knew. Firstpost. https://www.firstpost.com/world/openai-made-chatgpt-using-underpaid-exploited-kenyan-employees-who-forced-to-see-explicit-graphic-content-12053152.html

Steinfeld, K. (2020, June). Machine Augmented Architectural Sketching. Sketch2pix @ CDRF. http://blah.ksteinfe.com/200625/cdrf_2020.html

Steinfeld, K. (2021). The routledge companion to artificial intelligence in architecture. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367824259

Walker, S. (n.d.). Is artificial intelligence going to design your next building?. Arup. https://www.arup.com/perspectives/is-artificial-intelligence-going-to-design-your-next-building

White, T. (2018, September 3). Perception engines. Medium. https://medium.com/artists-and-machine-intelligence/perception-engines-8a46bc598d57

Wood, H. (2017, March 8). The architecture of Artificial Intelligence. Archinect. https://archinect.com/features/article/149995618/the-architecture-of-artificial-intelligence

-

Image credit:

Created with Midjourney

Comments